Human Development as a Pathway to Transformed and Peaceful Societies

In May, Inclusive Economies launched the second of its country-focused publications that investigates the links between human development and peace. With a focus on Zimbabwe, the research found inextricable links between governance, human development, and social cohesion.

At the time of its independence, optimism abounded about Zimbabwe’s potential to become a model African state that would leverage its abundance of natural resources towards the creation of a truly inclusive society. Sadly, this potential was squandered by weak and often predatory governance, leaving society with few prospects to prosperity. This has in turn created an environment of material deprivation that has pushed many, especially youth, to partake in risky activities that include illegal mining.

Kwekwe, an historical mining district in Zimbabwe, has now seen a large influx of people hoping to secure a livelihood from the growing illicit economy. In addition to desperate youth, these sites of illegal mining have also attracted other actors such as political elites, illegal gold buyers, unscrupulous middlemen and criminals. The involvement of criminal syndicates has led to an increase in violence and murders in the Kwekwe area. In response, youth and other actors are arming themselves with machetes and guns, forming gangs of their own to protect their access to the mines and a share in potential earnings.

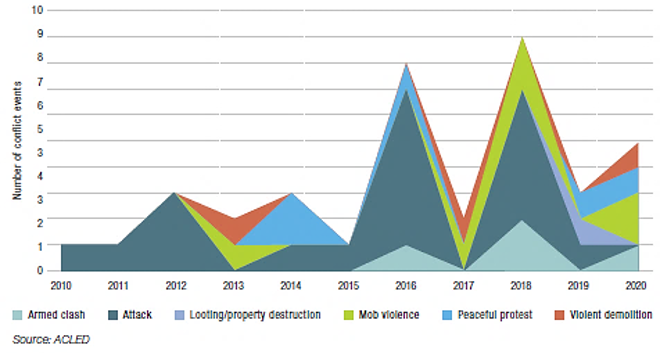

Figure 1: Conflict events in Kwekwe

Data sourced from the Armed Conflict Location and Events Data (ACLED) project and used for this research, shows that this environment has led to a gradual increase in conflict events over the last 10 years. The surge in violence is largely attributed to an increase in the number of ”attacks,” “armed clashes” and “mob violence.” Prominent actors in Kwekwe are gangs including a group locally known as Al Shabaab. They have strong connections to some senior ruling party officials from the province. Other criminal gangs include groups such as Mbimbos, Magombiro and Mabhudhi, who mostly specialise in raiding gold ore or demanding rents from artisanal miners.

Growth and expansion of artisanal small-scale gold mining (ASGM) can be connected to the economic decline, rising unemployment and poverty in Zimbabwe. To better understand these links, three epochs of governance were examined: 2000 to 2008; 2009 to 2013, during the government of national unity (GNU); and 2014 to 2020. Its findings point to a strong relationship between good governance on the one hand and sustainable peace and cohesion on the other. Importantly, it identifies good governance itself as a pivotal driving force for equitable and inclusive development.

At its core, the analysis illustrated that, under the GNU, improved governance created an enabling environment for inclusive development, with resultant benefits for peace and security. Using data from various sources, the researchers found that not only did governance indicators improve during the period of relatively improved governance under the GNU, but it also increased revenue and facilitated progress in human development. Additionally, working poverty decreased and trust in institutions improved, as did political stability. This highlights the crucial role that strong coordinated governance can play in securing a more peaceful and inclusive Zimbabwean society.

Unfortunately, the important gains made under the GNU have not been sustained after its demise in 2013. As a result, Zimbabwe has taken a path of deteriorating governance, economic decline and growing instability. The implications of the economic slowdown affected government revenue inflows against the backdrop of the strengthening of the now dominant currency, the US dollar. With reduced revenue, the government’s capacity to address the needs of critical human development diminished substantially. As a result, gains from the GNU era came under strain as the government struggled to meet its key obligations in the provision of public goods.

Since then, poverty levels have increased yet again, and the government has struggled to meet its public wage bill, which now consumes more than 90% of government revenue. This meant that government was now solely an employer and could no longer do anything else to promote human development.

These forces have resulted in a country with a highly informalised economy offering limited prospects for employment growth, forcing workers into an expanding informal and frequently illicit economy. Now, more money circulates in the informal sector because citizens have no trust in the formal economy, often pushing ordinary citizens to undertake risky action to secure a livelihood.

Looking ahead, the research puts forward a number of recommendations. Firstly, the size and extent of dependence on the informal sector by society necessitates proper consideration of macroeconomic policy; this can, after some time, facilitate the development of social safety nets for households whose main source of income is derived from informal trade. For example, developing employment-intensive industry with a focus on niche areas in the global value chain, from which state revenues can over time be leveraged to introduce a social security net.

The international community also has a role to play. In particular, it must seek ways to empower civil society and civil society organisations to advocate for themselves. This is especially crucial at a time when the civil space is becoming increasingly restricted.

In offsetting the dangers unlocked by these sites of illegal mining, is it critical that multilateral bodies like SADC and the AU support research and fact finding related to the illegal mining operations. Urgent attention and further research are required to understand better the circumstances and impacts of the ongoing and escalating illegal mining across the country.

In instances where chemicals like mercury are affecting water quality, immediate action is needed to safeguard people, aquatic life, wild animals and farm animals. Environmentalists and affected communities must also be supported to work towards sustainable solutions.

The international community should also consider targeted sanctions against the trade in illicit gold. This, coupled with human development programmes for youth forced into the trade due to a lack of other options, can help offset the illegal trade and its impact on youth.

If anything, scarcity lies at the heart of threats to stability, and it is crucial that the state facilitates an environment for private sector development and human development. This means that it ought to concern itself with improving governance so that its core function is service to society. Without this, scarcity will continue to threaten the social fabric of society.

The publication on Zimbabwe was preceded by research of the same cloth focused on Kenya.

Jaynisha Patel, Project Leader for Inclusive Economies